In my 2019 work, I orbited the camera lens home to what poet Adrienne Rich termed “the geography closest in,”1 my own body. A site of deep-rooted inquiry and resistance, it is always grappling with its intimate ties to various lands and belongings. All at once, my body is continually bound up with its subjectivities and experiences as a Chinese-Canadian immigrant, a settler on unceded, ancestral, and occupied Indigenous homelands, a woman of colour pulled between the shifting and competing tides of my diaspora.

Using self-representation and the physical and emotive weight of four foods, I offered up the idea of the corporeal as place, as event, where things occur and dissipate (or linger). My body became the ground for performing marginally demanding gestures. It was a temporary dwelling for ten kilograms of salt on my back as it dissolved into brine; a nest for hand dyed Chinese tea eggs before they spilled from my dress; a twisting frame with outstretched limbs unable to clean up an impossible spill. “While bodies do things,” scholar Sara Ahmed writes, things might also “do bodies.”2 The food items, like my accompanying video performances, were ephemeral in essence. Instead of offering gratification or nourishment, the foods are contemplative objects for my compounding griefs around predatory economies, resource extraction, sexual violence, loss, and yearnings for community care.

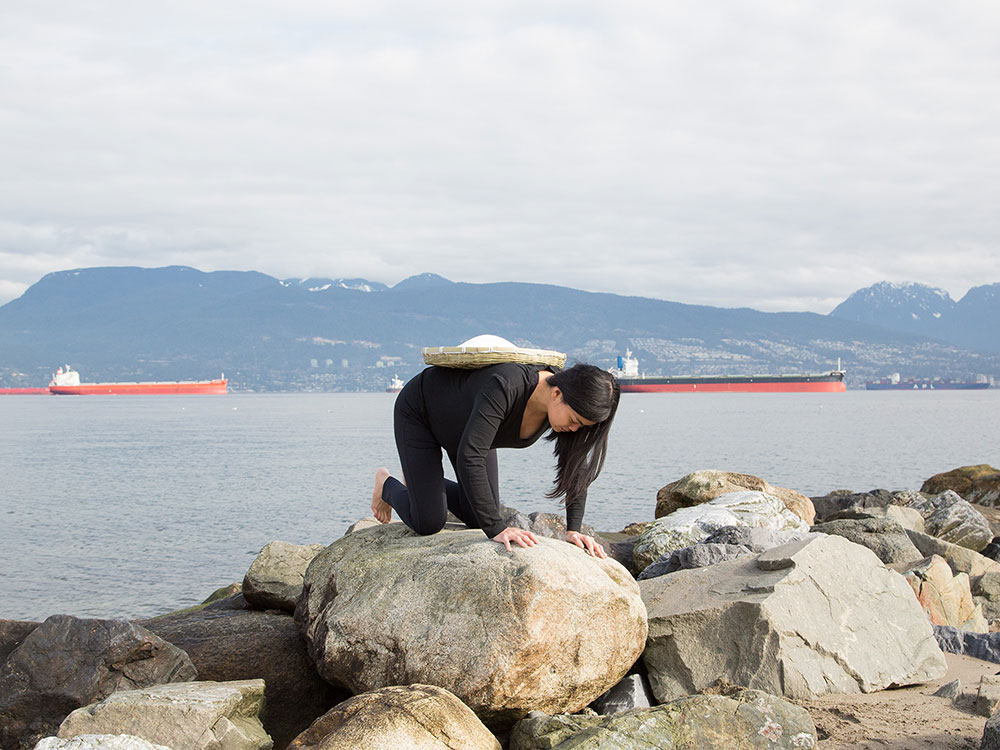

Murmur in the flesh, 30 in x 40 in lightjet print, 2019

The series was born out of a need to honour lived experience and raise consciousness around the integrity of land and bodies. In the face of historical and ongoing oppressions against Indigenous and other marginalized communities—as white supremacist capitalist patriarchal greed continually prevail—what roles can we take in questioning and acting against the complacency and complicity of settler-colonialism?

common wealth assumes its name from the old meaning of “wealth,” as in “well-being” or “welfare,” rather than the colonial use of “Commonwealth,” referring to the group of nations. It draws profoundly and proudly on my feminist of colour politic, its historical roots, and on ancestral memory. It is a long and deep gaze at what it means to exist in this body and on this particular land, while also growing new life inside of me.

Notes:

1 Adrienne Rich, “Notes Toward a Politics of Location,” in Feminist Theory Reader: Local and Global Perspectives, eds., Ruth McCann and Seung-Kyung Kim (New York: Routledge, 2003), 448.

2 Sara Ahmed, “Orientations Matter,” in New Materliams: Ontology, Agency, and Politics, eds. Diana Coole, Samantha Frost (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 245.

A murmur in the flesh, digital video (03:29) 2019

Following the renunciation of her Singapore citizenship and during a homecoming after eight years away, the durian that freely rests on Yow’s chest—swaying with each breath—collapses and pierces her skin off-camera. The fruit is emblematic of the nation and its conservative political climate, and its fall evokes the legal severing of ties with her homeland. Amidst the nostalgic yearning that Yow has always held for her motherland following immigrating to Canada, there is bitterness too. She recognizes how her acute overseas privilege allows her to be critical of the nanny-state and its exploitation of migrant labour, persecution of LGBTQ+ individuals, and romanticization of its colonial roots, all from afar.

How to become, remain, 30 in x 40 in lightjet print, 2019

Canadians want both and they can have both (take it with a grain of), 16 in x 24 in lightjet print

A luxury we cannot afford (are they worth their salt), 30 in x 40 in lightjet print, 2019

Crouching by the Salish Sea, Yow balances ten kilograms of salt, a nod to Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa’s pivotal 1981 anthology of radical women of colour writing, “This Bridge Called My Back.” Here, salt is significant for its ties to the climate crisis, oceans, bodies, preservation, purification, destruction, and above all, value. A violent pour of water eventually compresses the mound, adding further weight just as it drips off. Thinking much about people, worth, and resource extraction—including missing and murdered Indigenous women, water protectors, and the opioid crisis in this predatory economy and colonial nation-state of Canada—Yow questions what it might mean to care for others beyond one’s radius, and to recognize and challenge complicity and complacency in violence and oppression.

A luxury we cannot afford (are they worth their salt), digital video (03:14), 2019

Slow to warm, 16 in x 24 in lightjet print, 2019

The long and sudden of it (bodily integrity is integrity of land and water), 30 in x 40 in lightjet print, 2019

At a park honouring the British monarch, the artist visually compiles years of thoughts around realizations of sexual violence, pregnancy endings, and the onslaught of pipelines and dams. Nestling a heap of natural and red-dyed eggs in her dress, before letting them fall, was her way of processing the distinct, compounding griefs. Chinese red eggs symbolize birth, happiness, and prosperity and commemorate a child’s first month following birth. For Yow, learning and performing the cultural act of hand-dying eggs—with sheets of red calligraphy paper—then breaking them, was a way to mourn and subvert this traditionally celebratory gesture.

In our national interest, 30 in x 40 in lightjet print, 2019

A continuous passage, digital video (05:17), 2019

Wound and tear (how did you pronounce that), 16 in x 24 in lightjet print, 2019

Loss is most often invisible, and grief, so shapeless and brittle. Yow has been preoccupied with circular and organic forms, earthly mounds and hills, vessels that can be emptied and filled, notions of carrying and being carried. In thinking about the body and land as resource, she carelessly spills the contents of her bowl, letting it re-enter the earth. Milk—so culturally symbolic of life, wisdom, virtue, and as of late, white supremacy even—serves as a stand-in for oil, Canada’s gold. Its value has prompted the clearance of pipelines in the nation’s interest, despite much objection and without consensual reciprocity. In a related video, the liquid pours downhill as Yow attempts to soak it up with a towel. There is futility in cleaning up (and crying over) spilled milk, she asserts. Like an indelible stain, an oil spill can never be fully retrieved.